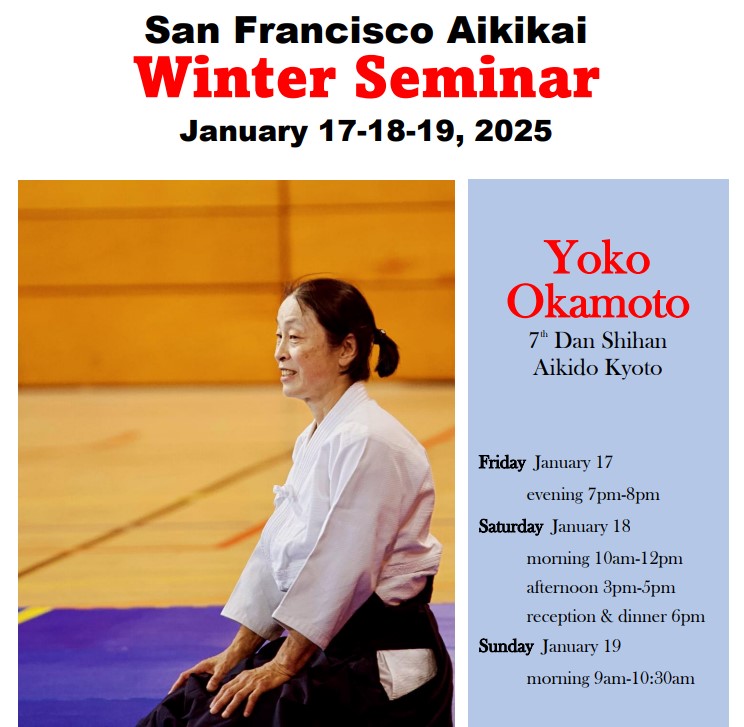

This (1/25/25) was the first class after the end of Kangeiko and after Okamoto sensei’s visit to Portland Aikikai. It was *scolding-look* a lightly attended class.

Favorably, lower attendance provides a forum to explain the principle of the axis of an encounter using a weapon.

The first explication: shomen-uchi from the draw to irimi-nage.

Both ukedachi and shidachi face one another with swords in the saya.

Ukedachi draws first and cuts shomen uchi.

Shidachi draws second and meets the ukedachi’s descending blade to adhere to it and ride the momentum to the bottom of the stroke while moving irimi to ukedachi’s shikaku. The moment the two swords meet is the axis of the encounter and should be the point of the arc of ukedachi’s sword at maximum extension. This is the neutral point where shidachi can move toward ukedachi’s flank because the swords define the vertical arc of danger. The weapons provide a visual and physical barrier that shidachi solves for by allowing his sword to shield (not block) ukedachi’s strike and afford a path of safety to ukedachi’s dead angle.

The mechanics of the draw requires precise use of the body – lowering the center while the left hand pulls the saya back and the right hand is fed the handle to then continuously draw to the top of the arc and simultaneously cut – and is a skill that must be developed. Aikido’s empty hand strike shomen should replicate the subtlety of an iaido draw. We did not have time to fully explore the draw, but rather, focused on the moment when the blades adhere, and then follow to the culmination of the arc of movement. At the bottom on the cut, shidachi’s blade is on top of ukedachi’s and therefore is in a tactically superior position – ready to ride to the opponent’s throat. The threat of the cut is precisely the same as the use of the shyuto in ai-hanmi katate dori irimi nage.

Both players should have a natural extension of their arms to keep the sword alive – full of the potential for action. The quality of connection should be obvious with a weapon in hand – each player should sense the vibrancy, a light tension where the downward pressure of shidachi’s blade holds ukedachi’s upward action. From this moment, shidachi embodies the principle of katsujinken to ride ukedachi’s blade with the mune (false edge) leading toward ukedachi’s neck only to then pass it and turn the kissaki down – live edge out – replicating the empty-hand irimi-nage throw. The bunkai should be obvious. Should shidachi turn the live edge in, the cut is lethal.

Once the basic form is understood clearly, then the focus shifts to the terminus of the cut. The swords ride to the bottom and remain in active connection, this is an extension of the axis of action away from the limits of the body – the connection has moved to the weapons themselves. This should be a familiar concept. When we drive, the car becomes an extension of ourselves in a similar manner. We learn to know when the front bumper is danger-close to an obstacle. The extension of “ourselves” is the boundaries of our vehicle. So the extension of self through a weapon should be as prosaic as driving. Thus at the bottom of the cut, when the swords ride upon each other, shidachi should be able to sense an active connection back to ukedachi’s center.

Weapon work should make the reason for connection explicit. If ukedachi drops his sword tip and breaks connection, shidachi can freely cut to the neck. Only an active and extended connection affords ukedachi any semblance of hope for survival. Using the active connection, shidachi can play with pressure to destabilize ukedachi just like irimi-nage. That was the somatic similarity I tried to draw out, to make Okamoto sensei’s use of the shyuto more obvious and emphasize the need and reason for active connection. Weapons make clear what is only implied in taijutsu.

The next explication: morote-dori kokyu ho.

Nage is armed, but the sword is in the saya. Uke approaches to control nage’s weapon hand. Sensing the hostile action, nage presents the arm forcing uke to grab at the top of an arc, allowing nage to lead uke’s energy down while nage moves offline (approximately 33-degrees). This is the same position Okamoto sensei use for gyaky-hanmi encounters. The importance of this initial movement cannot be understated because it defines the axis of the encounter. Nage’s hand flows vertically down the axis while uke cuts, thinking there is the possibility of controlling the arm. Nage’s hand must be knuckles toward the inside of their own lead leg. Nage: do not drop your head or bend at the waist! Back is straight, the hand on the saya lifts it skyward, pushing the handle down into the grasped hand, and simultaneously turns the saya blade down while drawing it back and nage shifts bodily back, allowing the grasped hand to grab the handle in order to draw simultaneously. A complex sequence of events that must be done smoothly to execute a clean draw of the blade. Once free of the saya, the blade arcs out and up so that nage’s arm is softly but fully extended. Nage follows the draw with the back foot in order to then pivot and cut. The result will be kokyu-ho because the blade bypasses uke’s neck (extends beyond it, because nage moves in, rather than steps back – which would result in uke’s death).

The specific lesson is that nage moves around the original axis, and minimizes the horizontal movement of the grabbed arm. To accomplish this, nage’s shoulders must be held softly and the elbow must never fold – resist the use of the bicep!

Wielding a weapon should increase the seriousness of training and lead to a better understanding of the principles informing the empty-hand (taijutsu) techniques.